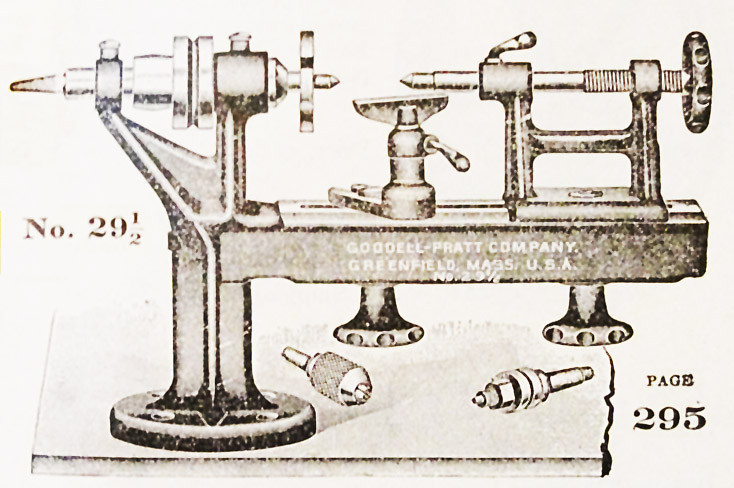

| The original Goodell-Pratt No. 29-1/2 polishing

lathe

was supplied with a graver tool rest and items for buffing wheels and

holding small round objects. |

Somewhere I acquired an extremely dirty slide

rest that looked hardly worth the effort of cleaning it up. Once I

exposed the original unblemished, unused surfaces, it became a perfect

match.

|

Here's the Montgomery & Co. (New York)

catalog image, page 199, ca. 1900, that is of this exact slide rest.

|

|

|

|

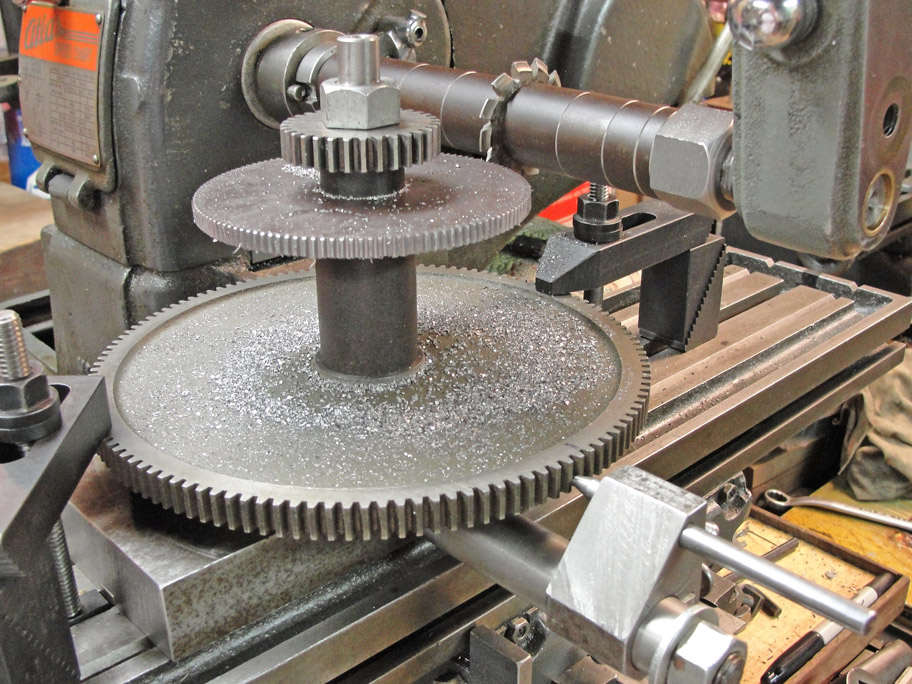

The gears shown below are all from my junk drawers, albeit with center

bushings made from scrap bronze tensile specimens. The shafts on

which

they run are all 0.229+ inch diameter. I proportioned the banjo

after

the one I made for the Sebastian treadle lathe.

|

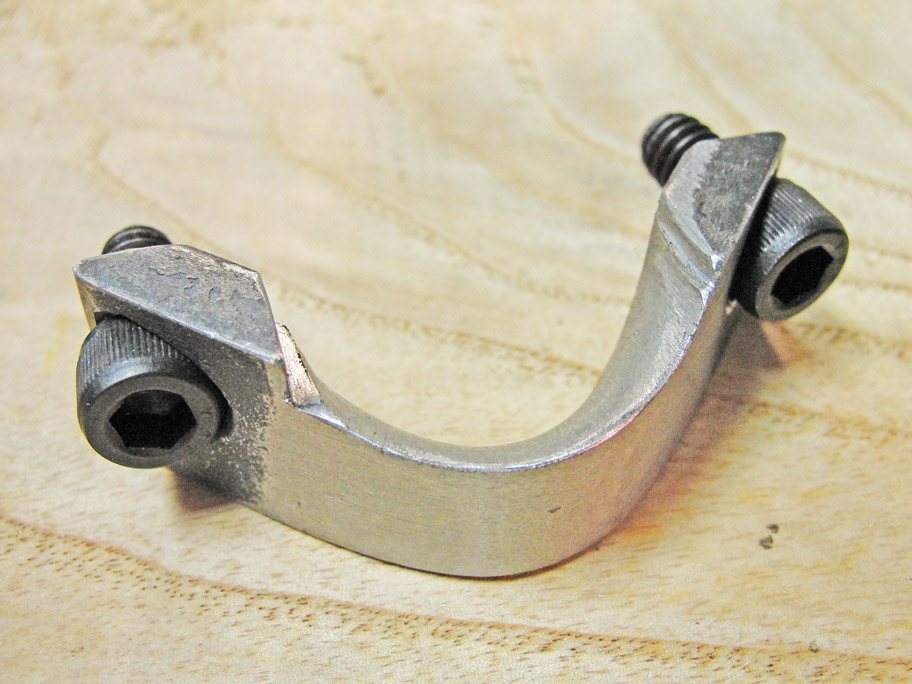

The brackets & banjo that hold the gears were made from angle iron

and plate steel about 1/4 inch thick. The T-nuts were made from bar

stock. The heavy bracket that fits the extreme left end of the

lathe

was machined from a block of steel and hand fitted by filing, as was

the body clamp shown at right.

|

The two clamping brackets are a fairly close fit to the lathe's

standard, but what saves the situation is the elasticity of the heavy

black paint, a.k.a. japanning. The attachment is quite secure and

does

not wobble or deflect in use.

|

|

|

|

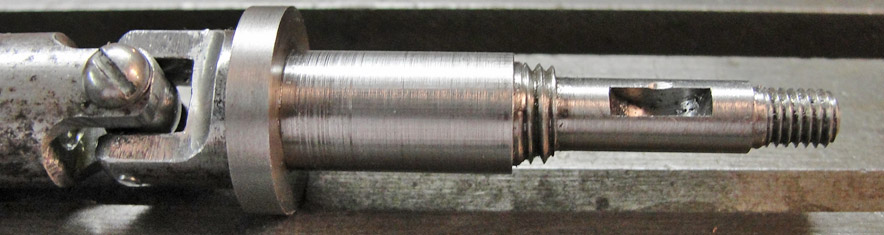

Shown below is the left-hand end of the drive

shaft with its Woodruff keyseat cut. The shorter thread is for a

retaining nut that minimizes end play. The longer thread is for

the thumb nut that retains the screw gear portion of the gear train, so

that it is easily changed for different feeds/threads.

|

The Woodruff cutter is the 5/16 inch diameter,

3/32 inch wide size that is quite delicate, so I held it in the Atlas

milling machine in a No.2 MT collet and clamped the drive shaft with a

my own special-made, one-time-only holding device.

|

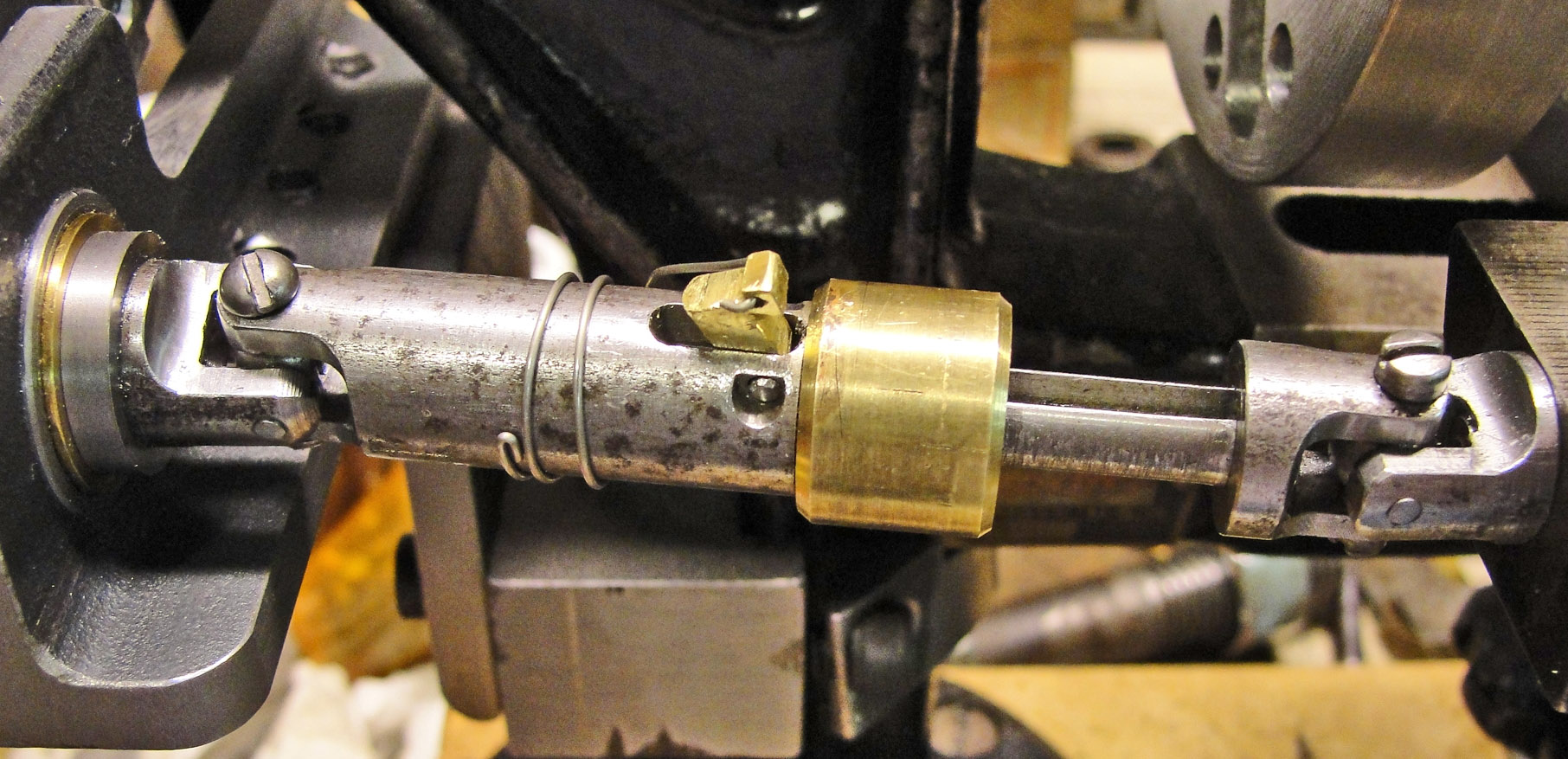

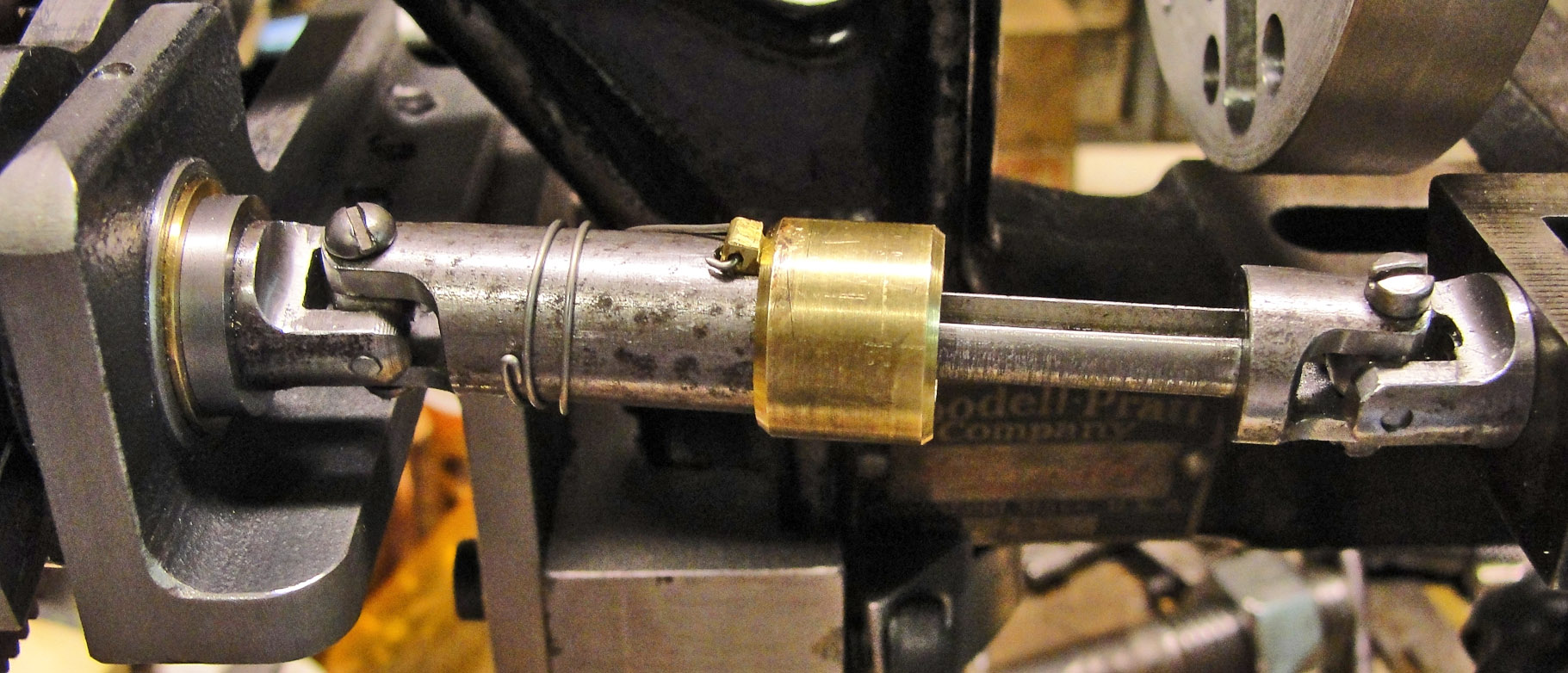

The drive shaft has to be disengaged in a

manner that lets me continue to run the lathe without disengaging the

gear train. The pawl device fulfills this requirement. The brass sleeve

has a friction device (two wire segments) in an annular space, so it

stays wherever it's put. The spring lifts the pawl.

|

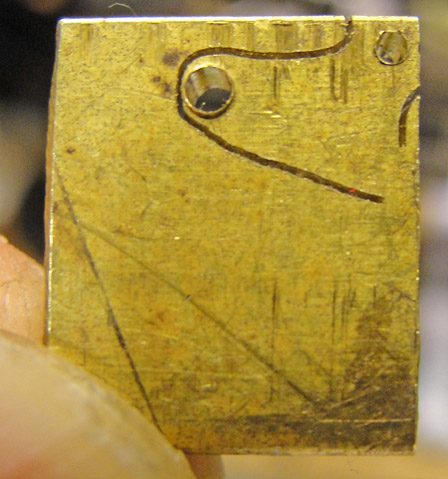

I cut the pawl with a jeweler's saw in one go,

with just a little filing to get it to function properly. It's made

from 1/8 inch thick brass plate.

|

|

|

|

|

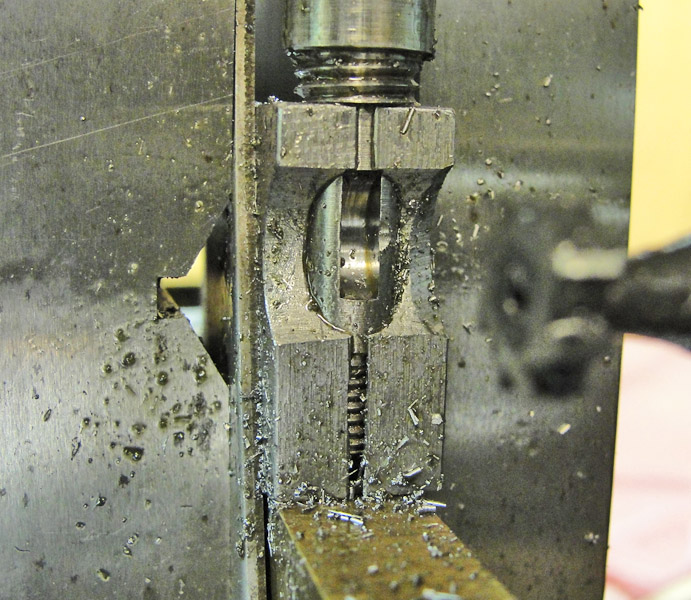

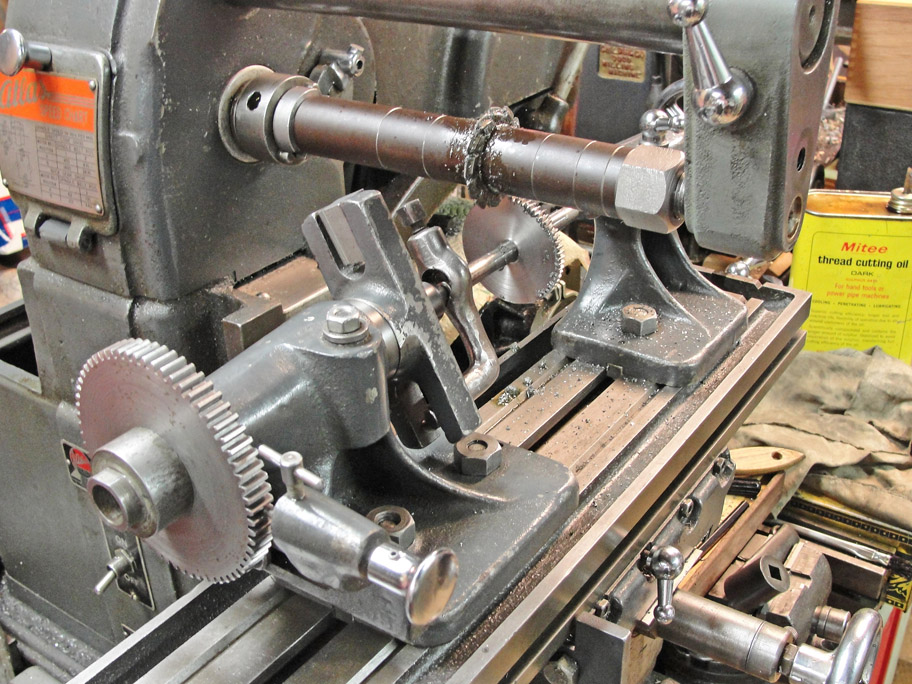

Presently I'm stymied by the lack of a gear

cutter for 35 to 54 teeth, but I do have the cutters that cover 55 to

134 and 26 to 34 teeth; below I'm cutting the 56-tooth gear, using one

I made for the Sebastian treadle lathe as a template.

|

Really large gears would require that I lower

the knee of the Atlas miller too far, so I made a fixture that allows

the template and gear being made to rotate on a common vertical

axis. It's more work to raise and lower the knee in order to cut

each tooth, though.

|

The gear train below, with a 40-tooth stud gear

and 64-tooth screw gear, uses a 56-tooth gear as an idler that also

causes the thread being cut to come out as a right-handed 32 tpi, as

the right-handed feed screw of the compound is 20 tpi.

|

|

|

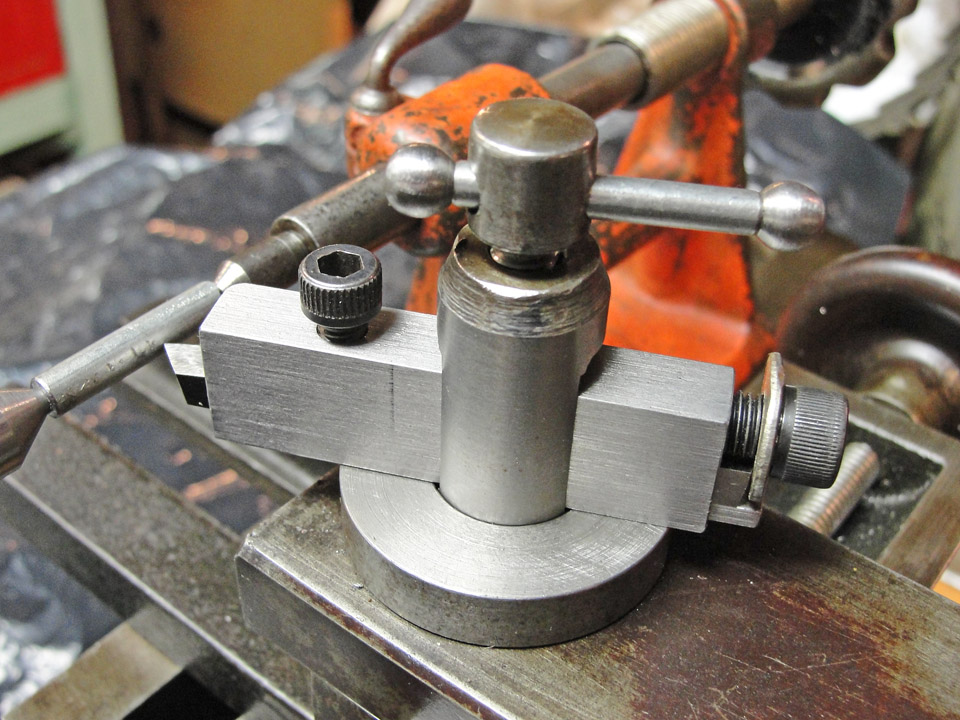

Also of note is the tool post, which incorporates a third

slide so that I can feed the 60-degree thread cutting tool at 29

degrees to the transverse axis so that the chip is cut mainly on one

side of the tool.

|

This lathe's compound rest has only two axes, and even some

three-axis tool rests have no means for setting the single-point

cutting tools feed axis at 29 degrees to the transverse axis as most

machinists know to do in order to get clean threads. The two tool

posts shown here provide that third axis in a way that avoids the need

for angular graduations on the third slide.

|

Perhaps you are wondering how I deal with the

task of setting the point of the cutting tool exactly at the center

height of the lathe ? That's taken care of by the Montgomery

& Co.'s tool slide, which as such an adjustment built into the

base. Just remember to set that before aligning the longitudinal

axis !

|

The main clamping screw of the external

threading tool post clamps the outer, channel shaped part of the tool

post. The socket head cap screw clamps the actual tool and holds it

down against a shim that's keyed to the thick washer. The main clamping screw of the external

threading tool post clamps the outer, channel shaped part of the tool

post. The socket head cap screw clamps the actual tool and holds it

down against a shim that's keyed to the thick washer.

The feed screw at right pushes the tool towards the work

at an angle of 29 degrees to the transverse axis of the coupound.

The Vee of the single point tool is rotated 29 degrees

from the feed axis so that proper setting of the tool with respect to

the work also sets the feed axis correctly.

|

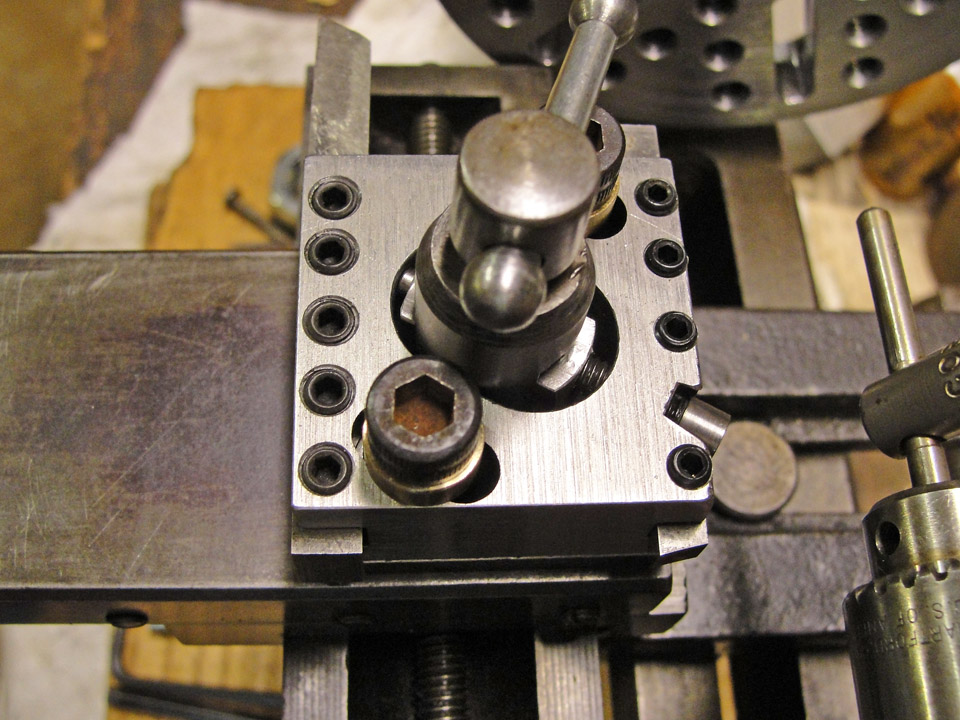

For the internal threading tool post shown at

left, the third axis of the compound is created by a slide between the

bottom plate of the tool post and the upper part that actually holds

the tool. The bottom plate is clamped with the main clamp, and

the pair of socket head cap screws clamp the upper part to the lower

part. Feed is effectuated by the socket head cap screw whose head

appears at the lower right hand corner of the tool post. The keys

between the upper and lower portions of the tool post run in slots

milled into both parts at 29 degrees to the transverse axis. For the internal threading tool post shown at

left, the third axis of the compound is created by a slide between the

bottom plate of the tool post and the upper part that actually holds

the tool. The bottom plate is clamped with the main clamp, and

the pair of socket head cap screws clamp the upper part to the lower

part. Feed is effectuated by the socket head cap screw whose head

appears at the lower right hand corner of the tool post. The keys

between the upper and lower portions of the tool post run in slots

milled into both parts at 29 degrees to the transverse axis.

|

As this is billed as a treadle lathe, I built a

suitable table and tried to invent a foot motion that could coast

without waving the treadle back & forth. This annular drive

fills that bill, as in the image below the center of the annulus is

lined up exactly with the axis of the flywheel's axle. The

flywheel can rotate freely at this position of the treadle (shown as a

mock-up only). Very hard to adjust ...

|

The annular drive can operate in two modes: (1)

With the treadle swinging in a wide arc so that the crank pin (running

on Torrington needle bearings) travels in a full circle; or (2) With

the treadle restricted to a swing truncated at the middle

(freewheeling) position, which causes the crank pin to run in a 180

degree arc, reversing the swing of the treadle arm twice per revolution.

|

I bored the two holes in the crank as exactly as I could

and then made an eccentric sleeve to allow for adjustment on erection.

I also had to allow for adjustment of the position of the

annulus so its arc of swing would pass exactly through the axis of the

flywheel axle. That was by trial & error ... tedious indeed.

Operation was very jerky at first and I only progressed to

an annoying level of jerkiness before I gave it up.

|

The annular

drive would have worked great, but for this fatal flaw: If allowed to

swing in the full arc, it would randomly try to reverse the flywheel's

direction of motion upon passing the center position if there was the

slightest hesitation. That brought the flywheel to an instantaneous

halt. The annular

drive would have worked great, but for this fatal flaw: If allowed to

swing in the full arc, it would randomly try to reverse the flywheel's

direction of motion upon passing the center position if there was the

slightest hesitation. That brought the flywheel to an instantaneous

halt.

So it had to be restricted to the half swing treadle motion, in

which the treadle would swing with next to no resistance for 90 percent

of the arc, so I had to press the treadle hard during only part of its

motion.

|

In

the end I just made a simple crank & foot pedal treadle

mechanism which works OK, as the lathe doesn't want to coast very long

anyway, due to the friction in the plain-bearing countershaft. The

shaft hangers are antiques in their own right. At low speed the

spindle turns at eight times the flywheel's speed; at the high speed,

the ratio is about twenty to one. I also made a numbered dial for

the crossfeed; I will eventually do the same for the longitudinal

feed. The drive belt that's presently turning the spindle has a

metal connector that's too large - it hangs up in the narrow clearance

underneath the smaller spindle pulley. Alignment adjustments for the

belts are easy but fussy; the leather belts came from my clothes closet.

I made no irreversible changes to the

Goodell-Pratt lathe; I did make a new spindle

with

a 3/4-10 threaded nose to

hold the four-inch faceplate that I made with thirty 1/4-20 tapped

holes and six Tee slots. I replaced the handles

on the feed wheels of the slide rest; I made no changes to the

flywheel, although I had to get creative to clamp it onto its 3/4 inch

axle. I did find it necessary to raise the tailstock by 0.015 inch

(with brass shims) in order to improve its alignment with the headstock

center. I'm looking for a small chuck that I can fit to the nose

of the spindle. The 30 by 30 by 30 inch bench knocks down to three main

parts that are easily transported. The lathe can be driven by

hand from the little wheel at the right-hand end of the countershaft,

which might make threading a little less stressful.

|

|

|